Humanist Perspectives: issue 153: The Appeal of Alternative Medicine

The Appeal of Alternative Medicine

Happiness and Science dawn though late upon the earth; Peace cheers the mind, health renovates the frame; Disease and pleasure cease to mingle here, Reason and passion cease to combat there, Whilst mind unfettered o’er the earth extends Its all-subduing energies, and wields The sceptre of a vast dominion there. —Percy Bysshe Shelley

photos in this article by Emrys Damon Miller

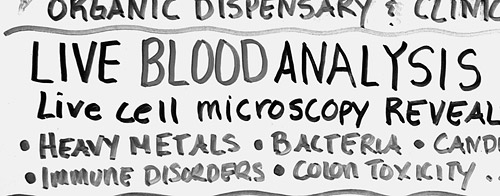

Happiness and Science dawn though late upon the earth… Shelley’s passage reflects the optimistic belief of nineteenth century intellectuals that the rise of science combined with universal education would bring a new age where superstition would wither, reason would triumph, and disease would be vanquished. And what has happened, two centuries later, as mind unfettered o’er the earth extends? While the world is awash in scientific knowledge and technology undreamed of in Shelley’s time, superstition and magical thinking, pseudoscience and anti-science are still found in abundance. As for health and illness, despite the astonishing advances made by medical science — gene therapy, MRI and PET scans, organ transplants, vaccines, laser therapy and many others — the popularity of ‘alternative,’ non-scientific and pseudoscientific therapies is mushrooming. Amongst them are: chiropractic with its root belief in a vital energy field that runs through the spine; homeopathy, which presumes that a substance that produces symptoms resembling those of a particular disease will cure that same disease when taken in vanishingly small quantities; naturopathy, with its conviction that the body is self-healing and only requires the requisite amounts of sunlight, air, water, nutrition and massage in order to overcome illness; aromatherapy, based on the presumed healing power of certain oils; craniosacral therapy, in which the balance and flow of a supposed craniosacral ‘rhythm’ are put into good order by the manipulations of the therapist; acupuncture, through which obstructions to the flow of a ‘vital energy field’ in the body are supposedly removed; therapeutic touch, in which the ‘life energy field’ of the patient is manipulated by massaging the air some centimetres above the body — a technique now taught in many nursing schools!

What is the appeal of these ‘alternative’ therapies? This would be easy to understand if they actually worked, if they lived up to their many claims of being able to cure all manner of disorders, including some that still stymie medical science. However, so far as careful scientific research can reveal, they are generally no better than placebos, and at times — as in the case of some herbal remedies or with high neck chiropractic manipulation — they may actually cause harm. If it is not therapeutic success that reinforces the appeal of these therapies, then what is it? Why do many reasonably educated people of normal intelligence put their health in the hands of therapists whose therapies derive from erroneous and/or occult beliefs about how the body functions?

There is really nothing new about all this, of course, for there has never been a time when logic and scientific evidence completely held sway over the public mind. Indeed, throughout the long history of modern medicine, nascent scientific reasoning has always had to struggle to keep superstition and supernatural belief at bay.

From earliest times, humans have striven to understand the world around them, and whenever possible, to regulate their environment to produce greater comfort and reduce risks to their wellbeing. Survival, nutrition and avoiding pain and suffering are of central importance to every people. Cerebrally endowed with the powerful ability to detect spatial and temporal patterns amongst objects and events, early humans slowly built up a collective knowledge base about health and survival that was passed from generation to generation: Do not eat mushrooms of a certain shape or you will die. Do not enter the river with an open wound or the piranha fish will devour you. Run for cover when the sky turns suddenly dark and the winds begin to howl. Of course, many of the patterns that were detected only seemed to be meaningful. Crushing an eagle’s egg at sunrise may have seemed to ward off a dreaded pestilence, reciting certain incantations over the rough image of an enemy may have seemed effective, sometimes at least, in bringing harm to that enemy; ingesting a particular herb may have seemed to have revived flagging muscles or a flagging libido. No one knew or probably even thought about how to eliminate spurious, meaningless, correlations amongst events. One takes the herb, feels better and then attributes the improved feeling to the herb itself, just as some well-educated people today consume mega-doses of vitamin C in the mistaken belief that it will prevent colds, and then attribute their being cold-free to the vitamins.

Systems of natural magic, involving remedies for what ails us and methods for influencing the world around us, developed in all ancient societies, and the beliefs associated with such magic have never entirely died away. Oddly enough, natural magic shares with science the axiom that there is an order to the world, a set of invariant rules and laws which if discovered and understood allow one to harness and control nature. However, despite its seeming effectiveness in situations where common sense was not sufficient, early humans were all too aware of the limitations of magic, for it seemed powerless in the face of catastrophe. Moreover, it could not offer succour with regard to existential anxieties, the same anxieties that plague so many people today: Why are we here? Why do storms, famine, and pestilence strike at will? (And if at will, whose will?) What happens when we die? How can a warm and animated body become lifeless in a moment; where is the personality now? And when that lifeless person appears in a dream, does that mean that he or she lives on? In the search for understanding, it was natural to come to believe that there is something about human existence that survives beyond the physical world. It was also natural to come to believe that there are other discarnate personalities who control those forces of nature that bring either plenty or famine, sunshine or storm, health or illness.

Magic and religion commingled as part of each society’s developing framework for understanding and treating illness.

Religion not only offered explanation and understanding, but offered another route to influencing the course of nature. Magic and religion commingled as part of each society’s developing framework for understanding and treating illness. If the prescribed magical poultice of root and herb did not cure, then perhaps an appeal to the supernatural beings who rule the world would. Again, our brains find patterns quickly, whether they are meaningful or not. Pray to Zeus or Odin or Coyote to be made well, and what happens? Some people will recover even if nothing is done, and their recoveries will seemingly offer strong evidence of the intervention of the gods. Those who do not recover fail to do so presumably because the gods were not moved by their importunate supplications.

It was not until the intellectual enlightenment of Ancient Greece that modern evidence-based medicine slowly began to emerge from the melange of myth, magic and supernaturalism. The intellectual strides made by those Greeks were monumental. For example, Hippocrates (460–377 BCE), often considered to be ‘the founder of medicine,’ rejected supernatural explanations and taught that all disorders — both physical and mental — have natural causes and are not caused by the displeasure of the gods, as had been commonly believed. With regard to mental disorders, he taught for example that epilepsy is a product of brain pathology, not divine punishment.

However, tempus fugit. The Greek empire declined and was supplanted by that of the Romans. Despite a rising tide of supernaturalism and unreason, all was not lost. Galen (129–198 CE), a Greek physician living in Rome, followed and promoted Hippocrates’ teaching. With regard to mental disorders in particular, it is remarkable that Galen espoused the modern view that it is therapeutic for a troubled person talk to an empathic listener! However, when Galen died, several centuries of enlightened Greek thinking about health and illness ended in Europe, and the continent gradually sank once again into superstition and supernaturalism. It is sobering and instructive to note that although Rome was the centre of the most highly developed, technologically advanced, and powerful empire the world had ever known, it had neglected to protect and nourish reason, and the world suffered for it. In any case, the Spirits were back with a vengeance, and as demons fought to possess each person’s soul, the Christian Church taught that illness was retribution sent by God, and thus a sick person was a sinner. Mental illness and epilepsy were attributed to possession by demons. Against this theological backdrop, the actual practice of medicine took many forms, and magic thrived once more. Some doctors relied on magical charms, others based their treatment on astrology, while others used herbal and magical remedies from the apothecaries.

However, while the Greek ideas about medicine had died out in Europe, they survived in Arabia and Persia, where medicine was highly valued by Islamic leaders and inquiry was encouraged. In 792, the world’s first mental asylum was built in Baghdad, and subsequently, hospitals were built across the Islamic world. By 931, physicians were required to pass examinations of their medical knowledge and skill before being allowed to practice. Avicenna (980–1037), an outstanding Islamic physician, neo-Platonist philosopher, mathematician and astronomer, penned a million-word encyclopaedia of medicine, known in English as Canon of Medicine, which became a standard medical textbook that was subsequently used in Europe until the 17th century. In his Canon, he summarized all available medical knowledge, and made his own major contributions, such as recognizing the contagious nature of tuberculosis, describing meningitis for the first time, discussing soil and water transport of diseases, pointing to the powerful influences of psychological factors on physical health, and making important contributions with regard to anatomy and paediatrics. He stressed a psychological approach to mental illness; he emphasized care and compassion, as did the Greeks, but also developed methods somewhat similar to behavioural treatments of the modern era.

With the onset of the Renaissance in Europe, the progressive ideas of the Ancient Greeks began to resonate again, alongside ancient superstitions, and as modern science began to develop, with its emphasis on testing theory against data, medicine began to make long strides towards understanding and conquering many illnesses.

By the end of the nineteenth century in North America, science-based medicine was supreme in most universities, but there were still many competing medical practices available, some of which were rooted in pseudoscience and superstition. While almost all Canadian medical training was provided in universities, physicians in the United States were trained by one of three systems:

- through apprenticing with a local physician;

- through privately-owned medical schools where students studied under the physicians who owned the school; or

- through the university system. Many types of medicine were taught, including science-based medicine, homeopathy, osteopathy, chiropractic and others.

However, the success of science-based medicine in overcoming disease had produced a belief in its superiority as an approach both amongst physicians and much of the public at large. In light of this, the Carnegie Foundation addressed the concern about the plethora of competing and non-science-based medical programmes by asking a non-physician, Abraham Flexner, to examine medical education in detail and make recommendations. His report, Medical Education in the United States and Canada, was published in 1910, and in it, Flexner recommended medical education along the lines of the then German model, focusing both on scientific research and clinical training. This report is considered to be the most important event in the history of American and Canadian medical education, for it set the course for modern medical education. As a result of the report, and Flexner’s unstinting efforts to promote its recommendations, about 80% of the medical schools that were in operation in the United States at the time were closed down, and high standards for medical training were established

When modern medicine offers safe, reliable treatments, people overwhelmingly opt for them.

This brief history reflects the battle between scientific reasoning and pseudoscience/magic/supernaturalism that has gone on for centuries in western civilization. That battle continues to this day, and the nature of that battle has not changed very much. At bottom, people care very much about health and illness, and no one wants to suffer or to see their loved ones suffer. No one deliberately self-deludes and opts for phoney treatment when effective treatment is available. When modern medicine offers safe, reliable treatments, people overwhelmingly opt for them. Very few would seek cataract treatment from alternative therapists when science-based medicine does such a good job. No one goes to a chiropractor to fix a broken leg. As it has been throughout history, people turn to therapies based in supernatural or magical or pseudoscientific beliefs only when conventional medicine does not respond to their needs. However, and this is important, those needs often go beyond narrow medical needs.

When people in large numbers turn to alternative therapies, as has been happening in recent years, this suggests that conventional, evidence-based medicine is failing to satisfy their needs. This dissatisfaction and the attraction to alternative therapies stem from a number of factors.

1. Disaffection with dehumanized, technology-dominated medicine. As noted at the time that Flexner wrote his report, the North American public was predisposed towards greater scientific rigour in medicine. While Flexner’s report brought very important reforms to North American medical education, it also produced changes that affect the delivery of medical care to this very day. Flexner urged that the training of doctors should be provided not by working clinicians, as in the past, but by salaried faculty with a ‘research function.’ The eminent Canadian physician and medical educator Sir William Osler saw a grave danger in excluding working clinicians in this way, and it turns out that he was right. As Medical Professor Angus Rae, writing in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, noted while Flexner brought science into medical education:

By banning the practitioner and relying on salaried researchers to train doctors, Flexner divided the profession and contributed to its decline in the public eye. Many now see physicians as more interested in the science of medicine than in patients themselves, one reason why millions seek satisfaction in alternative care. Attributing such kudos to research and disparaging clinical medicine has brought about a decline in interest in producing the well-trained generalist…

Not only did medical education tilt towards the scientific and away from bedside manner and people skills, there were other influences that helped push practitioners more and more towards becoming health technicians. As Dr James Le Fanu, in The Rise & Fall of Modern Medicine, wrote:

The effectiveness of the modern drugs that came tumbling out of the drug companies in the 1960s and 1970s led to the neglect of simpler, more traditional remedies and the dismissal of anything that did not fit the ‘scientific’ ideas of the nature of the disease… following the discovery of cortisone and other anti-inflammatory agents, the skills of rheumatologists revolved around juggling various toxic regimes of drugs in the hope that the benefits might outweigh the sometimes grievous side-effects. Meanwhile, all the other therapies for rheumatological disorders — such as massage, manipulation and dietary advice — were abandoned virtually wholesale, only to be ‘rediscovered’ by alternative practitioners in the 1980s.

Thus to some extent medicine, while focusing on science, may have lost its heart. Unlike interactions with the family doctor of a half-century ago, a visit to a modern physician is generally a very brief one, and typically terminates either with a prescription for pharmaceuticals or a referral for tests, for scans, or for a specialist’s opinion. Alternative practitioners on the other hand are always generalists who appear to understand your problem, who appear to be interested in you and your life, and who rarely pass you on to someone else.

2. Disaffection with power-based medicine. The traditional relationship between physician and patient has always involved an extreme imbalance of power, which has led to restricted communication. A 1988 USA study found that, typically, the physician initiates 99% of the utterances and asks 91% of the questions, determines the topics of discussion, and asks further questions before the patient has been able to answer the previous one. Further, the speech style of the physician is that associated with superior power, and most interruptions are by the physician, except when the physician is female. Such a power imbalance is rarely found with the alternative practitioner. Alternative practitioners typically strive to be socially engaging, and they provide a much more positive social interaction.

Other research shows that patients comply more when they regard the person treating them as caring, friendly and interested in them, and when that person makes definite follow-up appointments in order to monitor progress. Thus, a patient is likely to leave the alternative practitioner’s office with a sense that the practitioner has listened, understands, and knows what to do — again, some of the usual benefits of a visit to the traditional family doctor of a half-century ago. The alternative therapist is likely to satisfy needs for reassurance, respect, and being cared about, something that busy modern physicians often neglect.

3. Fear that the cure may be worse than the disease. Significant numbers of people have become worried about the long-term effects of medication, and of course, even some widely-used drugs have turned out to have lethal effects on some people. The fear of pharmacological treatment pushes some people to those therapists who cannot and do not prescribe medication.

4. Information overload and confusion: Too much knowledge is sometimes a dangerous thing. The explosion in medical and health-related information available through the media has produced what James Le Fanu has called the ‘worried well.’ Media coverage of various health risks and sundry disorders leads people to worry inappropriately about their health, and to consult their doctors unnecessarily. This produces frustration on the part of the doctor, which produces a frustrated and disappointed patient when the physician seems disinterested. On the other hand, alternative practitioners typically respond with interest and compassion to all concerns.

5. It seems to work. Many of the ailments that people take to alternative practitioners are those that physicians can do little about — chronic aches and pains, symptoms of an hysterical or hypochondriacal nature. The attention provided by the alternative therapist is of course welcomed, and the reassurance that the treatment will be effective may actually have a significant psychological effect.

Other medical conditions are self-limiting or cyclical in nature, and will improve whether one does anything or not. In such cases, anything at all that is done by way of treatment will seem to have been curative, producing the conviction that the treatment ‘worked.’ Consider this personal example, which involves magical thinking:

In 1988 while visiting China as part of a group on a speaking tour, I developed severe laryngitis, to the extent that I could barely speak. We had spent a week in Beijing, which was beset by smog at the time, and were about to leave that city and visit other centres in China. I was anxious to obtain some treatment for my throat before leaving, and as a result ended up in the outpatient clinic at the main Beijing Hospital. After a brief medical examination, the physician wrote out a prescription, which was filled in the hospital pharmacy. I received two medications, each labelled in Chinese and English. The first was for Erythromycin, an antibiotic. The second was for Shedan Chuanbeiye, described on the label as ‘Snake Bile and Tendril-leaved Fritillary Bulb Solution.’ The primary ingredient was snake bile, and the label went on to inform that this is an efficacious drug for various throat and bronchial conditions. Despite our translator’s advice to take the snake bile, something she always used when needed, I opted for the antibiotic, and sure enough, a few days later, I was right as rain. The antibiotic had done the job.

Or had it? When this anecdote was later reported in print, a physician wrote a letter to the editor stating that from my description of symptoms, I had almost certainly suffered from a virus, and that antibiotics do not touch viruses. He concluded that I had recovered spontaneously. Had the translator suffered from the same condition and taken her medicine, she would have attributed recovery to the snake bile, whereas I had credited the Erythromycin. In each case, credit is given to the form of ‘magic’ most familiar to us.

Thus, even when we feel better after taking modern medicines prescribed by a physician, we do not know for sure that it is the medicine that cured us. Our thought process is no more noble or rational than that of the person who attributes a cure to a homeopathic remedy, for we are putting our faith in the judgment of the physician, just as others have faith in the judgments of their homeopath or aroma therapist. We must remember that faith and clinical judgment are not enough. One individual or therapist cannot properly evaluate the efficacy of a treatment. Meaningful evaluation requires careful science with controlled clinical trials.

6. Alternative therapies offer hope. What takes most people to the physician’s office? Essentially, they want to feel better. They either want reassurance that they are not ill, or that the illness can be cured. Modern medicine has become very good at curing a wide variety of ailments that used to invariably kill people. It has also become very good at predicting when it cannot cure. Being told that there is nothing that medicine can do to cure your fatal illness or take away your chronic pain is unsatisfying in the extreme. Alternative therapists offer hope, and moreover they do not make predictions about death or perpetual pain and suffering.

7. The lines have been blurred between evidence-based medicine and alternative therapies. The use of the title ‘doctor’ by chiropractic practitioners, the coverage afforded for certain alternative therapies through private medical insurance and even, in some provinces, through the provincial health insurance plan, the usage of terms such as ‘alternative medicine’ and ‘complementary medicine,’ make it difficult for many people to distinguish the difference between alternative therapies and evidence-based medicine. Moreover, many members of the public are unaware of the pseudoscientific bases for most alternative therapies.

8. Promotion and persuasion. Some therapists, such as chiropractors and naturopaths, are well-organized and market their therapies very convincingly.

9. Post-modernism. So-called post-modernist philosophy is essentially anti-scientific in nature. It teaches that truth is not some objective reality, but rather, it is relativistic, it is whatever we choose to believe that it is. Such philosophy has had a pronounced effect both on some members of the general public and on people in some academic and professional circles dealing with health education as well. The nursing profession, for example, has in many sectors become dominated by postmodernist thinking which teaches that it is neither the physician nor the nurse who is the healer, and that healing comes from within, from the Self, ‘the Divine within each of us.’ The nurse’s job, according to this view, is to help the patient through teaching self-healing techniques and by using other techniques to manipulate and balance the patient’s spiritual energies — hence the appeal of Therapeutic Touch in many nursing programmes. Post-modernism essentially operates to negate the appeal of rationality and science, and to the extent that it is accepted, then alternative therapies with their focus on the self and ‘life energies’ are more attractive.

10. Lack of critical thinking. Finally, many people are simply uncritical and uninformed. They do not inform themselves about conventional medical treatments, nor do they inform themselves about those of alternative practitioners. In other words, they approach alternative therapists with the same uninformed and uncritical attitude that they have always brought to the physician’s office. Traditionally, modern physicians have been viewed as unquestionable authorities on disease and health. We just have to do what we are told. Bend over, take the injection in the hip and do not ask questions about it. Sore throat? Undress, lie down on the table; few patients ask why. That same non-critical attitude is easily exploited by the alternative practitioner, who often provides more gratifying responses than does the physician. Furthermore, again reflecting a lack of critical thinking, many people also believe that they do not need to go any further in evaluating the usefulness of a particular therapy than their own opinion. If it seems to work, it must be good.

Modern western societies have neglected the importance of teaching children the tools of critical thinking, while at the same time, popular culture has encouraged them to challenge every authority while treating their own opinions, informed or otherwise, as reliable sources of knowledge.

These are some of the reasons that alternative therapies have become so popular in recent years. In addition, the growing belief in the power of prayer to cure illness, particularly in the United States, and the view espoused in some fundamentalist circles that AIDS is God’s punishment for homosexuality, signal a threat to the continued importance accorded by society to a rational and scientific approach to disease and treatment.

Medicine is about more than curing illness; it is also about giving hope and comfort. Alternative therapies benefit both from the failure to temper the many fruits of scientific medicine with compassion and interest in the patient as a person, and from our collective failure to teach and encourage the critical thinking skills that would allow the ordinary citizen to question the pseudoscientific basis and exaggerated claims that characterize alterative therapies in general. To Percy Bysshe Shelley, in order for science to truly benefit humanity, it must be balanced with imagination and the human touch: “Whatever strengthens and purifies the affections, enlarges the imagination, and adds spirit to the sense is useful.” Modern medicine take heed! •

James Alcock is Professor of Psychology at York University in Toronto and a Fellow of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Books he has written or co-authored include Parapsychology: Science or Magic (Pergamon Press, 1980); Science and Supernature (Prometheus Books, 1990); Psi Wars (Imprint Academic, 2003) and A Textbook of Social Psychology, 6th Ed. (Prentice-Hall, 2004).