Late in May, an estimated 215 unmarked graves were reported to have been found through ground-penetrating radar on the premises of a former residential school in Kamloops, BC.

Late in May, an estimated 215 unmarked graves were reported to have been found through ground-penetrating radar on the premises of a former residential school in Kamloops, BC. About one month later, about 750 unmarked graves were reported on the Cowessess First Nation reserve in southeast Saskatchewan, near the former Marieval Indian Residential School.

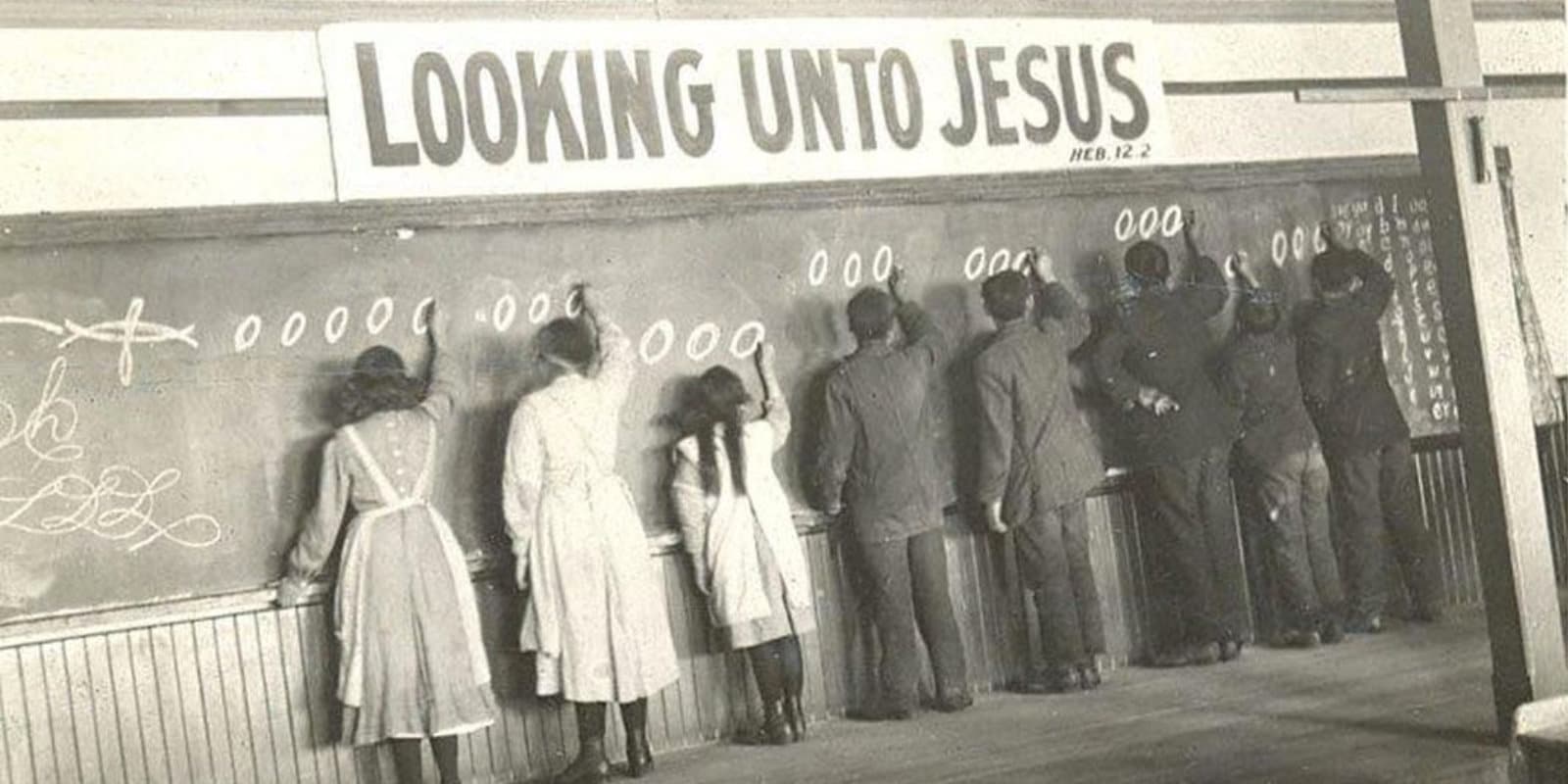

Indian residential schools mark a dismal chapter in Canadian history. The first such school was established by the Anglican Church in the 1830s and the federal residential school system began in the 1880s. Schools were run by the Catholic or Anglican Churches or denominations of Protestant churches. The purpose of the schools was to bring aboriginal children from tribes dispersed across the country to centres where they could be educated in the knowledge and skills needed to participate in the Canadian economy. Unfortunately, the residential school system in general engaged in a policy of aggressive assimilation to “take the Indian out of the child.” Children were often forbidden from speaking in their native tongues or engaging in their cultural practices. Many were also physically and sexually abused. About 150,000 children attended the more than 130 residential schools, the last of which closed in 1996.

The residential school system was established with good intentions, an education being thought essential for participating in an industrializing society, but the good intentions were permeated with paternalism, at a time when indigenous people were often called “savages.” There was not much concern about the devastating psychological consequences of uprooting children from their families and cultures into an alien system whose underlying purpose was to “reprogram” them. The Canadian government has recognized the wrongs that were committed. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established in June 2008 to conduct an enquiry into the residential school system and to settle class action lawsuits under the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement. In the same month, Prime Minister Stephen Harper gave a full apology to former residential school students on behalf of Canadians. For many decades, the Canadian government has been seeking, not always successfully, to establish a better relationship with Canada’s First Nations.

An estimated 6,000 children died while attending the residential schools. Some died of neglect, some died of exposure trying to escape, but most died of diseases such as tuberculosis, smallpox, and scrofula, and various influenzas, including the Spanish flu of 1918-19. The diseases to which students and staff at residential schools succumbed also took a major toll on indigenous populations not residing at residential schools, as well as on the white population. Most of the children who died at residential schools were buried on school premises. Their graves were often marked only with wooden crosses that decayed over time. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, whose Report was published in 2015, called on the government to help locate those unmarked graves. Therefore, while the discoveries of the unmarked graves in Kamloops and Saskatchewan were not happy events, such discoveries could not have been unexpected.

Much remains unknown about the recently discovered graves. Ground-penetrating radar detects disruptions in the ground and gives no information about the age, sex, ethnicity, or cause of death of the person in the presumed grave, nor about the age of a gravesite itself. The number of unmarked burial sites in Kamloops is now thought to be 200. In the case of Saskatchewan, the Cowessess First Nation has oral stories about children and adults being buried at the gravesite, which is said to have served a larger community, including people who attended the church or were from nearby towns.

Despite the scarcity of information about the graves, their discovery provoked a chorus of condemnations about Canada’s alleged genocidal policies toward its indigenous peoples. The media often carelessly, or perhaps deliberately, referred to the findings as “mass graves,” a term that implies genocide. These included the Toronto Star on May 31st (Mass impact from discovery of mass grave) and the New York Times on May 29th (‘Horrible History’: Mass Grave of Indigenous Children Report in Canada). Prime Minster Justin Trudeau called the findings “a shameful reminder of the systemic racism, discrimination, and injustice that Indigenous peoples have faced – and continue to face – in this country.” In a tweet on June 24th, NDP leader Jagmeet Singh included the words, “This is genocide.” The Global Citizen referred to the Cowessess site as a “Crime Against Humanity.” A large demonstration was held in downtown Ottawa on Canada Day to chants of “No pride in genocide.” Shortly after the Kamloops graves were discovered in May, the Canadian flags on Parliament Hill and other government buildings flew at half-mast, presumably on the orders of Trudeau. Government flags were still at half mast when the Saskatchewan graves were discovered on June 24th and remained there through Canada Day on July 1st, and beyond. The discoveries gave impetus to the already existing hashtag #cancelcanadaday, endorsed by officials at various levels of government, institutions such as museums, and many indigenous and social justice groups. Indeed, probably not a single jurisdiction, at the federal, provincial, or municipal levels held a Canada Day celebration this year.

Those accusing Canada of genocide and calling for the cancellation of Canada Day, and perhaps Canada itself, would do well to consider Cowessess Chief Cadmus Delorme’s observation that “This is not a mass grave site. These are unmarked graves.” Despite Canada’s checkered history with its aboriginal populations, it is wrong to use the term “genocide” to describe it. Dictionary.com defines genocide as “the deliberate and systematic extermination of a national, racial, political, or cultural group.” If the intent of Canada’s founders had truly been genocide, there would not be many indigenous people in Canada today. Given Canada’s earlier policies of forced assimilation, one could say it had engaged in “cultural genocide,” a term used in the TRC report. However, such policies have long been abandoned. The willing use by indigenous people of Western technology such as guns, snowmobiles, TVs, and cell phones should not be confused with forced assimilation.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that the discovery of unmarked graves of people few, if any, of whom were likely to have been deliberately killed has led to accusations of genocide. In 2019, the prime minster accepted the use of the term “genocide” by the inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Woman and Girls, even though according to the RCMP seventy percent of female aboriginal homicides in solved cases had been committed by people of aboriginal descent. Many were victims of domestic violence. The near-hysteria in response to the discoveries of the graves and the sensationalism surrounding them have not been without consequences. Statues of Sir John A. Macdonald and Egerton Ryerson (founder of what is now Ryerson University and instrumental in establishing the Ontario educational system), both involved in the establishment of residential schools, as well as of Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II, among others, have been toppled or defaced, as authorities for the most part looked on.

Far worse, close to 50 churches in Canada have been vandalized, desecrated, or set on fire, acts that could legitimately be called terrorism. The reactions to these acts of violence have for the most part been tepid and some have been shameful. BC Civil Liberties Association executive director Harsha Walia promoted arson when she tweeted “Burn it all down” on July 1st, following reports that two more Catholic churches had been torched. To my knowledge, she remains the BCCLA’s executive director. She also has not been charged with incitement, although attacking religious buildings is classified as a hate crime in Canada. Trudeau at least called the church burnings “unacceptable and wrong,” while claiming to understand the anger that led to them and decrying the “rise of intolerance and racism and hatred across the country.”

Unmarked graves are known to exist at the sites of residential schools and finding them is a stated objective of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The recent discoveries were made looking for such graves. The torrent of anti-Canada sentiment that has been unleashed and promoted by the discoveries neither helps the dead nor contributes to healing the living. But perhaps that is not the objective. Perhaps for some destruction is the objective, as toppled statues, burning churches and a civil liberties organization on board with “burning it all down” might suggest.

If the response to every civilization, nation, or tribe that had committed a wrong toward another group was to “burn it down,” there would be few societies left standing. Recognizing the wrongs of Canada’s past should not preclude celebrating its achievements. Canada Day is not just about honouring the past but also about our aspirations for the future. Will those who would cancel Canada come up with something better? If we don’t think so, we must not let them control the narrative about our country nor allow them to erase its history, even as we recognize its failures. If only we had leaders who understood that. ♦